Two issues ago I presented the belief that the axis of a leader’s success is your ability to recognize and operate from a place of your own authenticity. This place is the source of much wisdom and right action. There can be no leadership authenticity or growth without vulnerability. Trusting this vulnerability and tapping one’s authenticity becomes the scaffolding for greater impact, which I earlier suggested comes from three pursuits: 1) fostering an organizational culture of trust, participation, and reciprocity; 2) choosing how and with whom to inquire about future possibility and direction (aka, planning); and 3) engaging partners, donors, and investors in mutually meaningful dialogue.

The last issue addressed the first of those pursuits. Now, I’d like to turn our attention to the second: planning—think team planning, unit planning, organizational/enterprise planning, and/or community planning. The principles apply regardless of scale. Why? Because the planning process design reflects mostly unspoken assumptions. These assumptions determine the choices made in designing the process and become a window into how the leader leads.

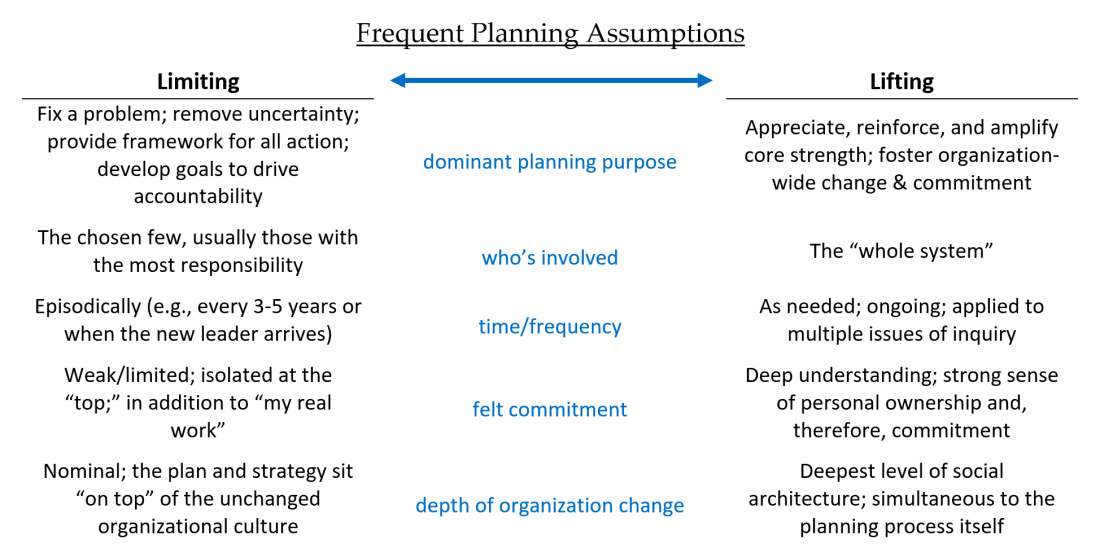

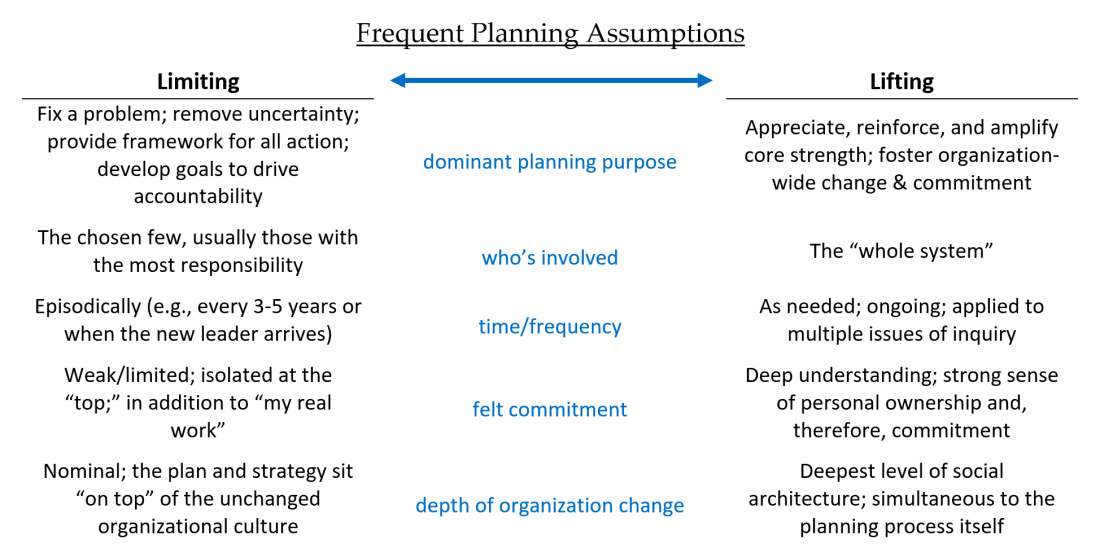

Some of the most common—and typically unspoken—assumptions framing choices in planning are as follows, which I’ve presented as poles on a continuum. The language of these poles may seem to represent stark dichotomies. These are not intended to represent some false dualism, as most of what I’ve observed in my long career of organizational planning is some hybrid point along each continuum.

Let’s amplify each of the assumptions above.

Dominant Planning Purpose

Planning is simply a process tool to achieve some bigger aim. Frequently, leaders embrace this process tool at predictable cycles: 1) around preparation for annual budget-development, which triggers annual operating plans being developed and performance metrics being attached; or 2) at “strategic” intervals (often, it seems upon inspection, for no better reason than “we’re at the end of our current x-year plan [fill in the time frame], and we need another one)”. Like any tool, its effectiveness is governed by the attitude and creativity of the user. Too often, planning is mechanical, uninspired, and unconsciously driven by the myth of control. Therefore, the resulting plan tends to provide limited traction and benefit to the organization.

Optimally, planning is inquiry and a change process simultaneously. The scope of the inquiry can be broad and far-reaching or narrow and short-term. The planning methodology matters little (operational, strategic, scenario, Hoshin planning, etc.), although some lenses, like appreciative inquiry, are intentionally focused on illuminating and reinforcing the positive core of the team, unit, organization, etc. This unconditional focus on “the best of what is” provides the scaffolding for a critical mass of organizational participants seeing and making changes in which they can believe deeply. This type of inquiry should produce an array of freedoms1 for the organization, namely:

- The freedom to be known in relationship

- The freedom to be heard

- The freedom to dream in community

- The freedom to choose to contribute

- The freedom to act with support

- The freedom to be positive

Leveraging the leader’s authenticity, then, is about her/his attitude of curiosity and a welcome embrace of a dominant planning purpose that fosters these freedoms for all participants and for the organization itself. The likely result is a widely shared path to the shared future that you all want most to emerge.

Who’s Involved?

I believe the best planning processes—those that mirror the right side of the table above—are those where many of the key stakeholders are involved throughout the planning process. Change agent Bliss Browne reminds us that we create and produce meaning rather than inherit it. Therefore, if planning is a tool for jointly creating meaning around an image of a more desirable future, then it seems fundamentally important that the process evoke real stories of that which gives life to the team, unit, organization, etc., when it’s at its best. These stories emanate from a broad spectrum of people who, if not involved in the planning process, big gaps in the socially-constructed and transmitted image of a new reality fails to take hold. That’s why we see that many of the most widely adopted planning methodologies (e.g., appreciative inquiry, scenario thinking, Future Search, World Café, etc.) revolve around getting “the whole system in the room.”

If we assume that our team, unit, organization/enterprise, etc. is one whole ecosystem (operating within and as part of an even larger ecosystem) then we’re a lot further ahead in designing our approach to planning and determining who to involve. Through such a lens, all the individual elements are part of an interconnected whole. Movement of one part triggers reinforcing or balancing movement elsewhere. Not only is this acceptance of whole system thinking important in any planning undertaking, it’s the starting point for determining whom to engage in the planning dialogue. No longer can we expect planning to be responsive if we have not engaged throughout the process those who design, execute, consume, endorse, and support and extend the work.

Unfounded fears of “tyranny of the majority” or “working to the lowest common denominator” or “halting the doing of the work so we can plan the work” are often just manifestations of cynicism and/or a tight grip on the myth of control. Just the reverse of these fears is true. By getting the whole system in the room2 (many, if not all, your employees, for example) you are working to liberate the latent power of the organization.

Trust is at the heart of appreciating this principle. That’s why I believe that it is incumbent upon every leader to be deeply introspective and identify the source of your own authenticity. Having done so, you’re much more likely to honor and trust that each individual stakeholder has their own version of equal value. Grounding yourself in this realization thereby opens you to the principle of dancing with systems3 and engaging a broad, diverse set of participants in the planning inquiry.

Frequency of Planning and Time Expended

Process improvement methodologies have taught us that the best processes are not necessarily episodic or cyclical but continuous. Such is true of organizational planning as well. If you embrace the notion that planning is intentional inquiry and simultaneous change, then you’ll be much quicker to adopt the belief that the planning process (tool) can be applied to any important organizational issue. For example, the process can be applied to an issue as broad as envisioning the impact of the organization in a new endeavor and/or to one as “narrow” as donor/investor/partner relations.

The beauty of leaders adopting the posture of the right side of the table above is that each planning initiative is directly contributing to nourishing a culture of competence, a widely shared perception of change as real work (not add-on stuff), and acceptance of responsibility. From this leadership commitment comes a long view of building and reinforcing the organizational ethos that embraces change as a means of demonstrating the positive core. Ultimately, the organizational speed of adaptation accelerates, in part because networks of communication and commitment become pervasive.

Sound a little too ideal to you? If so, you may be falling prey to any number of mindset blocks: a) projecting because of prior bad experiences with planning processes and cultures; b) believing that planning is the leader’s prerogative (alone) and the opportunity to “provide” direction; and/or c) a belief that planning should be episodic and its result monumental rather than meaningful daily and continuously relevant and cascading. One of the surest ways of getting out from behind one’s individual and organizational ego is to apply the right planning process much more often. In so doing, you’ll liberate the power of your people, remain agile in a constantly changing marketplace, and routinely contribute to the positive transformation of people, product, and planet.

So how much time should you be willing to invest in such a process? This might be a rhetorical question; however, it seems to me that any planning process that produces the six freedoms noted above is worth the requisite time in dialogue. Surprising to many leaders is that design of the process (including determining the optimal focus of inquiry and assuring the system’s representatives are co-designing the process with you) often takes as much or more time than the “planning” itself. One mentor of mine used to tell me that this work is counter-intuitive: going slow at the front end enables speed in execution. That wise advice is echoed in another common refrain, “if you want to travel fast, go alone; if you want to travel far, go with others.”

Felt Commitment

What good is any plan if few are committed to its complete execution? Not much, obviously. Yet, how often do we see planning processes that are thinly veiled undertakings of a “top-down” orientation where a vision and strategies (adaptive decisions) are communicated out to employees who have little, if any, buy-in. If this is such a common observed shortcoming of planning, why do so many of us continue in the same way? I believe that planning is about far more than charting direction. It’s equally about illuminating who we are at our very best and about how we will be in relation to one another and to our work. If your planning process is steeped in that principle, I believe you’ll find internal and external stakeholder commitment to be solid and sustainable. Planning through that lens builds trust equity, a necessary asset in a marketplace that demands quick turns and many about-faces to stay responsive and relevant.

Let’s go back to my original premise that leader leverage is most possible to the extent that the leader acts in alignment with her/his source of authenticity—your own positive core. The most committed and disciplined leaders, having illuminated and reinforced their own inner source, act in ways that evokes the same introspection in others. There’s lasting power in that. Further, it requires fewer control mechanisms designed to prod people into preferred behavior. Let’s face it, you and “they” can smell how negatively manipulative those mechanisms and metrics can be anyway.

Depth of Organization Change

During my work with organizations and my review of common literature on organizational change and leadership, there seems a widespread shared blind spot to the necessary locus of change and transformation to produce more desirable organizational outcomes. Often, the unconscious answer is “they” need to change…rather than I need to change. Alas, we can shrug this off as another illustration of the human condition. However, the more contemplative among us—those intentionally focused on a continuous learning path toward wise/right action, transparency, and reciprocal trust…aka, authenticity—are more likely to accept that world changers are self-changers first.

I believe that the leader’s greatest responsibility is to develop people and in so doing inquire with curiosity about what’s possible if each individual (and the organization) were to magnify and amplify their positive core—the vital elements that gives life to that person (and organization) when s/he is (they are) at their very best. This is the path to sustainable organizational change at a deep level. These are the organizations who focus unapologetically on their strengths, opportunities, aspirations, and results (SOAR).4 While they don’t ignore weaknesses and threats, they come at them from a different vantage point. Collectively, then, these people and organizations pursue real transformation and build resilience. Organizations in the vanguard of this thinking differentiate through a steadfast focus on self-management of their teams, explicit pursuit of wholeness, and a clarity, and continuous manifestation, of organizational purpose.5

Conclusion

Certainly, much attention is given the seeming ideal state of having a charismatic leader in place. Wall Street’s love affair with stories of superhuman titans of leadership and miracle turnaround experts unconsciously reinforces the myth that the single leader is the key to all success. My experience, however, leads me to conclude that the best leaders recognize, value, and trust the collective insight and wisdom of the people throughout their organization. They also realize that they can’t hope to manifest something powerful and liberating throughout the organization if they’re not first fully conscious of, and grounded in, their own inner truth and humility. At times like these when competitive pressures are fierce and imagination is essential, leaders must recognize that none of us is as smart as all of us. What’s possible if we planned our shared future grounded in that belief?

###

Leveraging Leadership Authenticity – Conversations 2017

Several years ago, I decided one way to leverage my own passion and contribution to wise leadership was to hold space for its deeper exploration among people seeking their own clarity and deepening their own leadership purpose. Conversation 2017 is one such contribution. Each Conversation is a coherent package of components over a 9-month period that includes one immersion workshop/retreat, reflective readings before and after the retreat, participation in moderated audio conference calls among the learning cohort, and individual virtual coaching throughout the period.

Nominations are currently being sought for the two Conversations 2017 scheduled to date:

- Portland, Oregon – July 12-14 – hosted by Providence Health and Services

- Minneapolis, Minnesota – September 27-29 – hosted by CohenTaylor Executive Search Services

Contact me to learn more, to nominate someone for consideration in either cohort. A limited number of scholarships will be available in each offering for gifted leaders unable to afford tuition. In so doing, together we can support some of the most vital work being done in community despite deep resource limitations.

###

1Cooperrider, D.L., Whitney, D., and Stavros, J.M., (2008), Appreciative Inquiry Handbook for Leaders of Change, Crown Custom Publishing: Brunswick, OH, pp. 27-29.

2Avoid the temptation toward literalism, believing that de facto, any and every planning discussion must involve EVERY stakeholder in the same way in the same place at the same time. While there are many examples of large-group retreat designs (some including groups in multiple locations) where thousands of stakeholders participate in real time, there are also countless examples of variations to handle volume without sacrificing engagement.

3See Donnella Meadows’ Dancing with Systems, in The Systems Thinker, Vol. 13, No. 2, March 2002.

4For more information on the SOAR lens, see Stavros, J., Cooperrider, D., and Kelley, D. L., (2003), Strategic Inquiry –> Appreciative Intent: Inspiration to SOAR – A New Framework for Strategic Planning

5Laloux, F., (2014), Reinventing Organizations: A Guide to Creating Organizations Inspired by the Next Stage of Human Consciousness, Nelson Parker: Brussels, Belgium.